What The Economist Didn’t Say

January 23, 2026

By Ed Augustin

Ever since it was founded in the 19th century, The Economist has enjoyed a cozy relationship with political and economic power in Britain. The magazine champions elite interests and scorns social justice.

“Cuba is heading for disaster, unless its regime changes drastically,” an article The Economist published in November, is a case in point. The piece rehashes tired clichés about Cuban socialism while ignoring the elephant in the room: U.S. economic warfare that has never been fiercer. The 1,600-word article mentions “the embargo” exactly once — and only in passing.

This is disingenuous.

“To ignore the U.S. blockade — now the longest and most punitive economic war in modern history — is not merely intellectually dishonest; it is propaganda masquerading as journalism,” professor Isaac Saney, coordinator of the Black and African Diaspora Studies program at Dalhousie University in Canada, wrote on Facebook. “For 65 years, Washington has set out to… cripple Cuba’s economy, deny it resources, isolate it from global finance, block food, fuel, medicine, and investment, and punish any country or business daring to engage with it. This is not a metaphorical war; it is a structural, economic, and psychological war designed to produce the shortages The Economist now reports as though they were natural phenomena.”

Belly of the Beast’s Corrective

By ignoring the context, The Economist obscures understanding. Here’s our corrective:

The Economist: “Electricity goes on the blink in most places for at least four hours a day.”

Tragically, the reality is even worse: most Cubans endure daily power outages of well over 12 hours. The Economist doesn’t bother to ask why.

The island has been suffering a fuel crisis since the U.S. government began sanctioning oil tankers to the country in 2019. The measures remain in place today, raising the cost of fuel needed by the island’s decrepit power plants to generate electricity.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuela have driven the decline in Venezuelan oil production. In 2013, Caracas sent Havana almost 100,000 barrels per day; last year, Havana received a daily average of under 30,000 barrels per day. This fuel lifeline has been severed in the last month after Trump’s enforcement of “a total and complete blockade” of sanctioned oil tankers. Seven tankers transporting Venezuelan oil have been commandeered.

Last year, Mexico has become the primary supplier of oil to Cuba, with President Claudia Sheinbaum describing the shipments as part of her government’s humanitarian efforts in the Caribbean and a long-standing policy of Mexico.

Perhaps most importantly, so-called “maximum pressure” sanctions — imposed by Trump during his first term, maintained by Biden, and intensified in the last 11 months — have succeeded in their aim of bankrupting the Cuban state. Economists estimate that on top of the embargo, these new measures cost the country billions of dollars per year. Cuba currently spends more than half its money importing food and fuel. Goring state revenues leaves the government with less money to buy fuel on the open market, to maintain power plants and to invest in renewable energy.

No wonder Cubans are suffering from the worst blackouts the country has seen since after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Economist: “According to the Social Rights Observatory, a Spanish-backed think-tank…only 3% of Cubans can get the medicine they need at pharmacies.”

Until 2019, Cubans could get just about all the medicine they needed in local pharmacies at affordable prices. But since then, they have suffered chronic medicine shortages leading to empty pharmacy shelves.

The Economist’s numbers are again off the mark.

Cuban Prime Minister Manuel Marrero Cruz told Cuba’s parliament last December that 29% of medicines were available in the necessary quantities at hospitals and pharmacies.

Family doctors and pharmacists interviewed last month by Belly of the Beast say that since then, the situation has gotten worse: They estimated they are now receiving between 20% and 25% of the medications their communities need.

“Three percent is an absurd figure,” said Dr. Mayda Mauri Pérez, president of BioCubaFarma, the state-run biotech and pharmaceutical group that produces most of the island’s medicines. “Anyone making this claim is lying and will not be able to substantiate it.”

Screenshot from The Economist article.

The statistic comes from the Social Rights Observatory, which The Economist presents as “a Spanish-backed think-tank.” The magazine fails to mention that the organization is a U.S. government cutout: It forms part of the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights, which was granted $2.2 million between 2019 and 2025 by USAID for Cuba “democracy promotion” (a.k.a. “regime change”) programs.

The Social Rights Observatory did not respond to questions about how it arrived at the 3% figure.

The Economist: “Tourism, once a pillar of the economy, has collapsed…after the covid-19 pandemic the industry never recovered.”

Covid was a major blow for all Caribbean economies dependent on tourism. But for Cuba, it was a double whammy. The island was hit by the pandemic and potent new U.S. sanctions at the same time.

Following Barack Obama’s historic detente, tourism on the island surged to historic highs. Conversely, following the unprecedented hardening of U.S. policy, tourism tumbled from 4.75 million visitors in 2018 to just 2.2 million last year.

Successive administrations have designed policies to maximize damage. Trump banned U.S. cruise ships from docking in Cuba and stopped flights to all Cuban cities except Havana in 2019. The Biden administration quietly rescinded ESTA privileges, or electronic visa waivers, for citizens from 40 countries who travel to Cuba. That means a British reader of The Economist who visits Cuba would be barred from going to the United States unless they first obtain a visa — a lengthy and uncertain process.

A blood-stained Cuban flag on the profile image of The Cuban Observatory of Human Rights on X shows this is a partisan organization. #SOSCuba, the hashtag below, helped spark nationwide protests in Cuba in July 2021. The hashtag was retweeted more than a million times by bots beyond the island’s shores.

For most Europeans, traveling to the U.S. is an easy process. They qualify for the U.S. Visa Waiver program (ESTA), meaning they just have to fill out an online form. However, U.S. law denies normally eligible individuals access to ESTA if they have visited countries on its State Sponsors of Terrorism list. Cuba has been on the list since 2021 even though there is no evidence Cuba sponsors terrorism.

The Emperor's New Clothes

The Economist: “‘This system is so screwed up it’s unfixable,’ says a 52-year-old taxi driver who would leave if he didn’t feel obliged to look after his sick mother. ‘All you can do is get rid of it and start all over again.’”

For The Economist, calls to replace socialism are par for the course. The magazine was founded in 1843 by James Wilson, a British hat manufacturer who would go on to become a politician and banker. From the get-go, the magazine consistently opposed progressive politics on the grounds of advancing “free trade.”

In the 19th century, The Economist advocated for abolishing Britain’s meager state welfare system known as the Poor Laws, policies that, according to the magazine, only encouraged “improvidence, idleness, fraud, and lying.” It opposed the Factory Act, which limited child labor to nine hours per day. It even moralized that steps toward public sanitation in Britain’s cities should be opposed: “There is a worse evil than typhus or cholera or impure water, and that is mental imbecility.”

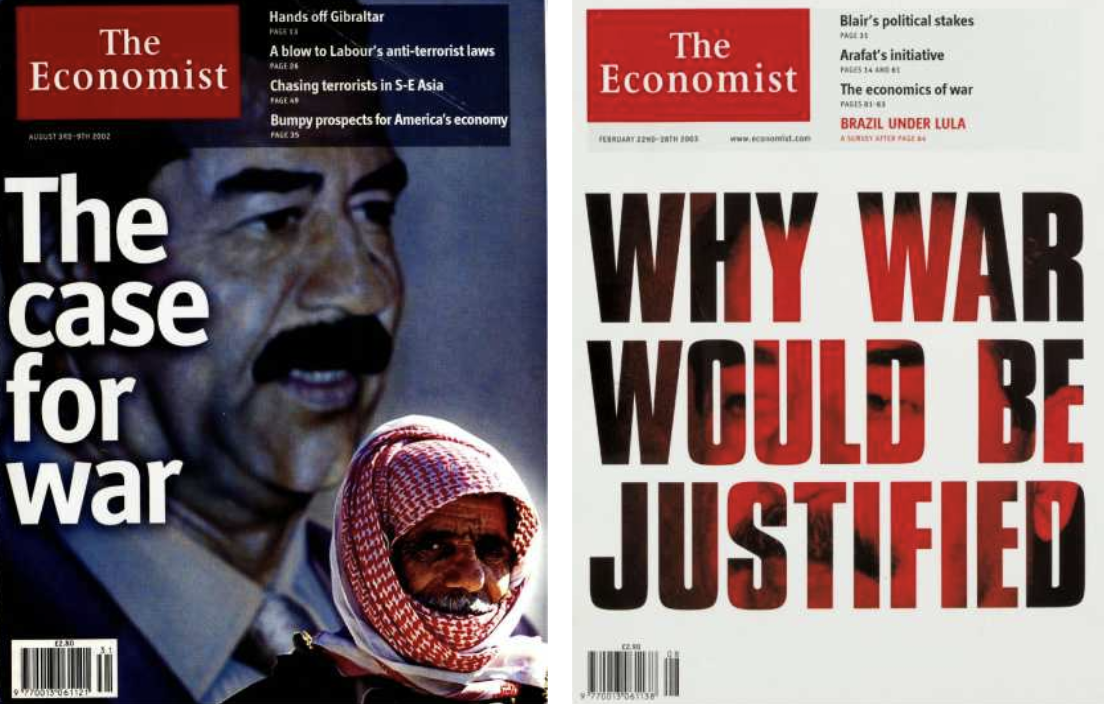

The Economist has regularly cheerled state violence to crack open foreign markets. “We may regret war,” mused a 1857 editorial as British ships shelled Chinese ports during the second Opium War, “but we cannot deny that great advantages have followed in its wake.” More recently, it backed the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2011 bombing of Libya.

James Wilson, founder of The Economist

The front cover of two editions of The Economist in 2002 and 2003

In Latin America, The Economist celebrated the 1973 coup in Chile that replaced Salvador Allende’s democratically elected leftist government with Augusto Pinochet, who oversaw the murder of 3,000 people and the torture of tens of thousands more. A 2013 Economist article derided food and public health programs in Venezuela that extended fundamental human rights to millions of people, casting them as state “handouts.”

Serious critiques of Cuba — especially of the economy’s glaring internal problems and the current level of suffering on the island — are invaluable. But despite its smug self image as a magazine that marshals the facts to arrive at authoritative conclusions, when it comes to Cuba The Economist shows no interest in rigorous inquiry. Instead, it cherry picks data, uses dodgy sources and airbrushes the main driver of Cuba’s economic and humanitarian crisis. This is not journalism. It’s dogma.