No, Cuba Wasn’t “Propping Up” Maduro

January 10, 2026

This story was written in collaboration with Drop Site, a non-aligned, investigative news organization dedicated to exposing the crimes of the powerful.

By Ed Augustin and Reed Lindsay

Cubans observed two official days of mourning earlier this week after a contingent of its security forces were massacred guarding Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro. Flags were flown at half-mast, and concerts were canceled.

“No country has the right to invade another,” one woman told us on the streets of Havana. “Those Cubans were there at the request of the Venezuelan government to protect Maduro… The blood we’ve shed unites us.”

Are people on the island afraid that Cuba could be next?

“What’s happening in Venezuela can happen to any Latin American country, so I’m afraid,” said Adriannys Poll, a 19-year-old college student studying microbiology. “I want to graduate, but you don’t know what could happen in the next three years of Donald Trump’s presidency.”

“Everyone knows it’s about oil. I don’t think they’ll come and bomb Cuba,” hoped one person.

“We’ve lived under threat our entire lives, even [of] an invasion. And we defeated them,” said another.

What We Know About the Cubans Who Died

One hundred people, including civilians and security forces, were killed in the U.S. attack on Venezuela, according to Venezuela’s Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello.

The Guardian reports it took the U.S. two hours and twenty-eight minutes from the time its helicopters touched down in Maduro’s compound in Caracas at 2:01 a.m. to seize the former president and his wife. Maduro, the paper reported, had tightened his security measures leading up to his abduction and was relying more heavily on Cuban bodyguards.

But the lack of a response from the Venezuelan military and the disparity in the death toll — the U.S. reported no casualties — have fueled speculation about betrayal.

Venezuela’s acting President Delcy Rodríguez fired General Javier Marcano Tábata, who headed the Directorate General of Military Counterintelligence and was responsible for Maduro’s security. Rodríguez herself has come under question due to a report that she and her brother, President of the National Assembly Jorge Rodríguez, had been leading talks in Qatar with the Trump administration about a “more acceptable” alternative to Maduro in the months leading up to the U.S. attack.

But the imbalance in casualties may have more mundane explanations.

“The casualty rate may reflect the superior U.S. technology and a clear order for U.S. troops to fire at anything or everything they see,” said Fulton Armstrong, former U.S. national intelligence officer for Latin America, who emphasized how U.S. forces, arriving undetected, had the element of surprise on their side.

“The Americans obviously came in with a great deal of firepower and simply overwhelmed them,” said Hal Klepak, Professor Emeritus of History and Strategy at the Royal Military College of Canada and a former NATO analyst who also served as an advisor to that country’s foreign and defense ministers. “That’s an American tactic throughout Latin American history over almost two centuries. You don’t go in with the minimum; you go in with the maximum.”

Venezuela’s Defense Minister Vladímir Padrino on Sunday read a statement from the Bolivarian Armed Forces, accusing the Trump administration of “murdering in cold blood a large part of their security team, soldiers and innocent citizens.”

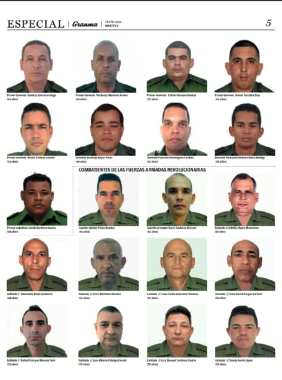

On Tuesday, Cuba published the headshots, names, ranks and ages of the 32 Cuban officers killed by the U.S.

The list included colonels, lieutenants, majors, captains and reservists ranging in age from 26 to 60.

But questions remain about how the Cubans were killed.

What Were Cuban Security Forces Doing in Venezuela?

After the election of socialist President Hugo Chávez in 1998, Venezuela quickly became Cuba’s closest ally. Early in his term, Chávez signed alongside Fidel Castro the Cuba-Venezuela Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement that saw Cuban specialists lend their expertise in Venezuela in the fields of culture, education, health and more.

Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world, but its healthcare system had always faced medicine and staff shortages. Cuba sent thousands of doctors and nurses to work in Venezuela, where they were paid many times the tiny salaries they earned in Cuba. In exchange, Venezuela shipped oil to the island.

For years, U.S. officials complained that Venezuela was propping up Cuba with subsidized oil. Then, in 2019, the first Trump administration flipped the script.

That year, Trump called Maduro a “Cuban puppet.” Vice President Mike Pence accused Cuba of keeping the Venezuelan people “hostage.” U.S. Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams said Venezuela was a “colony” of Cuba, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed the island was “the true imperialist power in Venezuela.”

Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton, who oversaw a failed effort with then Senator Marco Rubio to bring about regime change in Venezuela, claimed there were 20,000 Cuban “thugs” propping up the Maduro government. “Maduro would fall by midnight” if not for the Cubans, Bolton told reporters in April 2019. (For more, see the second episode of our award-winning documentary series, The War on Cuba).

That narrative gained new traction in recent months as the Trump administration ramped up political and military pressure on Venezuela.

In October, Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado likened the presence of Cuban advisors inside Venezuela to an “invasion” and made it part of her push for U.S. military intervention.

“I don’t think it’s any mystery that we are not big fans of the Cuban regime, who, by the way, are the ones that were propping up Maduro,” Rubio told NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Sunday.

No credible evidence that Cuba had thousands of troops in Venezuela has been presented.

What has been verified is that thousands of Cubans have gone to Venezuela to work as doctors and nurses, as well as teachers and sports coaches.

One of them is Dr. Lyhen Fernández Baez, a urologist who is the mother of Belly of the Beast journalist Liz Oliva Fernández. (Liz conducted a mother-daughter interview with her, asking about her experience serving on a medical mission in Venezuela in Episode Two of the War on Cuba.)

Manufacturing a Security Crisis

For months, the Trump administration said its deadly boat strikes and military buildup in the Caribbean were aimed at fighting “narcoterrorism.” The Justice Department claimed Maduro was leading a drug trafficking organization called “Cartel de los Soles.”

But this week, the administration quietly dropped that claim in a revised indictment, acknowledging that Cartel de los Soles isn’t a real cartel — even as Maduro still faces narcoterrorism and cocaine trafficking charges in a federal court.

Concocting far-fetched accusations to legitimize hostility has been the U.S. government’s go-to playbook for decades when it comes to Venezuela and Cuba. For example, the island occupies multiple State Department blacklists, accused of carrying out human trafficking via its medical missions and even sponsoring terrorism despite consensus to the contrary in the U.S. intelligence community.

The close relationship between Cuba and Venezuela has also provided fodder for neoconservatives like Abrams and Bolton, who both have decades of experience scheming up ways of overthrowing governments around the world.

Abrams, convicted for “withholding information from Congress” during the Iran-Contra Affair, was “the crucial figure” in Washington during the bungled Venezuela coup d’état that briefly deposed President Hugo Chávez from power in 2002, according to The Guardian. (The New York Times on Wednesday released a 52-minute interview with Abrams to help their readers understand “what is actually happening in Venezuela.”)

Bolton, who once falsely claimed that Cuba was developing biological weapons, argued in 2019 that Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela form a “troika of tyranny” and a “triangle of terror” in the Western Hemisphere, reminiscent of the “axis of evil” rhetoric employed during the George W. Bush years.

Led by Bolton and Abrams, the Trump administration did not abandon the claim that Venezuela propped up Cuba; it simply doubled down on the reverse accusation.

U.S. officials have toggled between portraying Caracas as Havana’s benefactor and Havana as Caracas’s puppet master — contradictory narratives that nonetheless converged on the same policy goal: sweeping “maximum pressure” sanctions on both countries, including measures aimed at cutting Venezuelan oil exports.

“Patently False” Claims

Security experts say U.S. government claims about Cuba’s influence in Venezuela are grossly exaggerated.

Ben Rhodes, a former U.S. deputy national security advisor who played a key role in negotiating the normalization of U.S.-Cuba relations during President Barack Obama’s second term, has disputed the claim that Cuban military personnel in Venezuela numbered in the tens of thousands.

“The only way you get to those numbers is to count doctors as security officials,” Rhodes said in an interview conducted in 2019.

“The number of Cuban security officials alleged by the U.S. government was patently false,” said Armstrong. “The vast majority are civilian doctors, teachers and coaches, and many are women.”

“We know that there were indeed Cubans in Maduro’s security detail, but perhaps now, we can also put to rest that the Cubans ‘ran’ Venezuela’s security plan because they apparently didn't have any indication of the attack until it was upon them,” he added.

Cuban-Venezuelan cooperation deepened after the 2002 coup, with the Cubans assisting in the creation of security services and military intelligence capacity in Venezuela, according to Klepak.

He added that Cuban officers posted within the Venezuelan armed forces’ command system have also long been connected to natural disaster relief efforts.

“The UN has often hailed Cuba's [disaster response] system as the best or one of the best in the world and a model for other countries. Venezuela is prone to natural disasters, but its forces had a dismal record for dealing with them. Thus, asking Cuba for assistance was obvious,” he said. “But the idea that this tiny military presence is in any way an occupying army or that it is anything like 1,000 people, never mind 25,000 people, is simply politically motivated.”

Cuba’s Long History of Resisting U.S. Intervention

It’s not surprising that Venezuela would turn to Cuba for help in defending itself from U.S. aggression.

The island has weathered a U.S.-backed invasion, acts of sabotage, repeated terrorist attacks and numerous assassination attempts on Fidel Castro. Cuba’s intelligence service is renowned, in particular for repeatedly outmaneuvering the CIA.

Decades ago, Cuba was also known for an internationalist military that punched above its weight, sending military contingents to face off against U.S.-backed forces in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.

While Abrams was secretly arming right-wing paramilitaries to overthrow the left-wing Sandinista government in Nicaragua in the 1980s, Cuba sent their Marxist allies military advisors.

When the leftist New Jewel Movement came to power on the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada after it won independence from Britain, Cuba sent military personnel to support the fledgling government. The Reagan administration called Grenada a “Cuban-Soviet colony” in 1983 and invaded it.

Cuba’s most successful foreign military intervention was in Angola, where Cuban soldiers fought with the left-wing People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). From 1975 to 1991, Cuba deployed hundreds of thousands of troops to the country — by far the largest overseas military engagement ever conducted by a Latin American country. Cuba was also credited with helping bring about the fall of apartheid in South Africa.

“The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom and justice unparalleled for its principled and selfless character,” said Nelson Mandela during a visit to Cuba in 1991.

But when the Soviet Union disintegrated, Cuba’s economy went into a tailspin, and its military internationalism ended.

“The Cuban armed forces were cut massively from between 270,000–290,000 in the 1980s to between 55,000–60,000,” said Klepak, adding that Cuba’s military has been reduced to home defense with little to no capacity to project force beyond the island.

An Inconvenient Truth for Regime Changers

Over the years, Cuba has become one of the U.S. government’s most reliable security partners in the Caribbean.

Since the 1990s, Cuban and U.S. armed forces have collaborated closely on counternarcotics operations and efforts to stop illegal migration, according to Klepak. Cuba’s strategy, Klepak argues, has been “to create a body of people in the U.S. government who see Cuba as a natural and effective ally in security issues.”

With the days of large-scale Cuban military internationalism long gone, regime change proponents are left with an inconvenient truth.

According to Klepak, “however much both sides try to downplay it, until the first Trump administration, the closest security relationship that Cuba had was with the United States of America.”

Now, with Maduro out of the picture and nearly three dozen Cubans dead, the claims that Cuba is propping up Venezuela appear more absurd than ever.

The opposite claim — that Venezuela is propping up Cuba — may also no longer be true.

In 2025, Venezuela was shipping less than 30,000 barrels a day to the island, about 70% less than what it was sending a decade earlier. This fuel lifeline has been further cut in recent weeks as the Trump administration ordered “a total and complete blockade” of sanctioned oil tankers. In December, the U.S. started seizing Venezuelan oil tankers at gunpoint.

In recent years, Mexico has become a major supplier of oil to Cuba, with President Claudia Sheinbaum portraying the shipments as part of her government’s humanitarian efforts in the Caribbean and a longstanding policy of Mexico.

The U.S. is pressuring the interim administration in Venezuela to stop oil shipments to Cuba, but it is not clear yet what will happen to other aspects of the two countries’ relationship or whether the Cuban doctors, nurses and teachers who are serving on humanitarian missions in Venezuela will be forced to return home.

If they are, they may be replaced by U.S. oil executives.

Rubio said on Wednesday that the administration was about to finalize a deal with the Venezuelan government to “take all the oil,” adding that the U.S. had “a lot of leverage” because of its continuing blockade on Venezuelan oil exports.

Meanwhile, the heads of Exxon Mobil, Chevron and ConocoPhillips met with Trump Friday to discuss his plans to “run” Venezuela and control its oil industry.

At the meeting, Trump continued to vex those looking for an end-game behind his assault. “We are open for business,” he said. “China can buy all the oil they want from us, there or in the United States. Russia can get all the oil they need from us.”

Amba Guerguerian and Liz Oliva Fernández contributed to this article.