Is Cuba’s Military Really Holding Billions Overseas?

An Interview with Economist Emily Morris

August 27, 2025

Earlier this month, the Miami Herald published an article claiming that it had obtained a “trove of secret accounting documents” proving GAESA, the Cuban military-run conglomerate, was hoarding $18 billion.

Herald journalist Nora Gámez Torres built a series of sweeping claims on top of her findings, which were framed as a bombshell discovery. GAESA, she claimed, is amassing wealth “at the expense of the Cuban people” and “squeezing the state” out of funds that could be used for healthcare, energy and food.

Cuban-American hardliners have since cited the article to justify the Trump administration’s economic war on Cuba and to push for harsher sanctions.

But here’s the catch: It's not at all clear GAESA is holding $18 billion – or anything close to it. To get to that figure, the Herald relied on shaky assumptions.

We take a deep dive into the numbers and the Herald’s reporting with Emily Morris, Honorary Senior Research Associate at the University College London Institute of the Americas. Morris has been studying the Cuban economy for more than three decades, and has worked at the Inter-American Development Bank and the Economist Intelligence Unit.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Examining the Herald’s Reporting

Before we dig into the Herald article, can you explain what GAESA is and why it’s such a big deal?

GAESA is a conglomerate controlled by the Cuban military. It was created in the 1990s during Cuba’s economic collapse after the fall of the Soviet Union known as the “special period.” The idea was that military officials trained in business practices would run state-owned companies more efficiently at a time of severe scarcity and economic crisis. Since then, GAESA has grown tremendously and is now a huge conglomerate and it's clearly important because it runs a lot of companies that play a significant role in the Cuban economy. It’s also not transparent: the public does not have access to details of how these companies operate.

What did you make of the Herald article and the 22 “secret documents” it claims to have obtained?

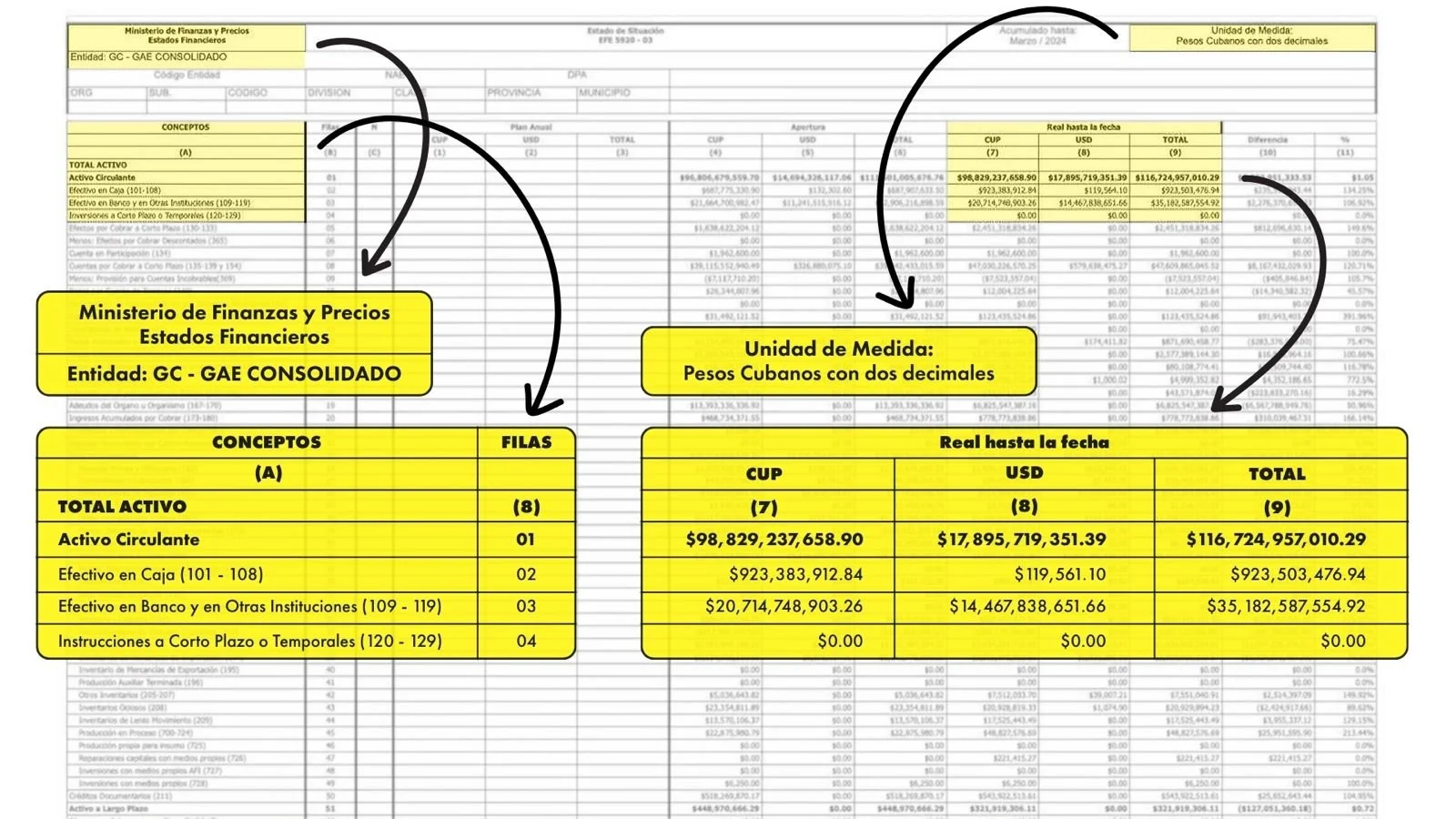

The Herald published four tables they created themselves that purport to show GAESA’s assets and liabilities, sales and profits, and contributions to the government’s budget in 2023 and 2024. But we haven’t seen any of the original financial statements since the Herald didn’t publish them and we don’t know for certain whether the documents are genuine. There is only one blurry screenshot of a balance sheet from March 2024 that lists GAESA’s assets. Based on the spreadsheet, the Herald concluded that GAESA’s total dollar assets were $17.9 billion in March 2024 and that $14.5 billion was supposedly being held in GAESA’s bank accounts. But it’s not at all clear that that’s the case.

Breaking Down the Numbers

Do the documents show that GAESA had $18 billion in cash stashed away as the Herald claims?

No, they don’t seem to. When we look at the one original document we have access to – the blurry screenshot – it’s not at all clear that the figures in the “USD” columns are actually dollar values. Some of the columns say CUP [Cuban pesos] and some say USD. The Herald is assuming that the USD column represents U.S. dollars, and that’s where it got the $17.9 billion figure for GAESA’s total assets in March 2024. At first glance, this would seem to make sense. But there are a few reasons to question this. Under Cuba’s accounting system, even when income is received in foreign currency, official financial statements will present this income after it’s been converted into CUP at the official exchange rate. Also, it would make no sense to mix currencies that are not the same value and then add them up as if they were the same. The statement has a “TOTAL” column, which adds the amounts in the “USD” and “CUP” columns. This indicates that all these columns represent amounts in one currency – Cuban pesos. And if you look at the header of the blurry screenshot, it clearly indicates that the currency used for the entire statement, including the columns that say USD at the top, is Cuban pesos. If that’s the case, then the USD column would represent GAESA’s U.S. dollar assets converted into pesos, most likely at the official exchange rate of 24:1. So, GAESA’s total assets would not be $17.9 billion dollars, but 17.9 billion pesos, which in dollars is $746 million. And instead of GAESA holding $14.5 billion in its banks, it would only be holding $603 million.

Click image to expand.

Assessing the Claims

The Herald concludes that GAESA has become a shadow government that is “squeezing the state out of the funds it could use to invest in healthcare, energy and food.” Could this be true?

There is nothing in the data that was published to support any of that. There’s nothing in the balance sheet or the tables that indicates that GAESA is “squeezing the state out of funds.” That seems to be quite a leap. The data simply show GAESA’s assets, they don’t show that money is being taken from the state.

The Herald cites economist Pavel Vidal, who suggests that GAESA has unofficially assumed the role of the country’s central bank, and that the alleged $18 billion in assets is the country’s international reserves. Is that possible?

We’d be speculating to say that GAESA is holding Cuba’s reserves based on this information, especially given the questions around the data, which indicate that the dollar amounts are a fraction of those reported in the Herald. The level of Cuba’s international reserves is an official secret. When I worked for the Economist Intelligence Unit, my colleagues and I had to estimate the reserves in order to determine Cuba’s risk rating according to the EIU model. I would ask officials at the Central Bank, but they would tell me in no uncertain terms that it was classified information. The reserves figures used in those reports were therefore always estimates (and footnoted as such), pieced together from the available evidence.

Why would information about Cuba’s reserves not be publicly available? Is this normal?

No, it’s not at all normal. Cuba is exceptional because the circumstances are exceptional. Cuba’s finances are kept secret because they are handled as a national security issue given that Cuba is facing relentless U.S. efforts to force political change through economic sanctions.

What about GAESA? Why does it also need to be confidential?

It’s logical that state-run Cuban companies engaged in international trade would operate through offshore entities, details of which are kept confidential, not because they intend to take them out of the reach of government auditors but in order to avoid U.S. sanctions. This certainly limits accountability, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t government oversight. In fact, while the Herald states that GAESA’s books are out of the reach of government auditors, the financial statement it published as a screenshot has a “Ministry of Finances and Prices” heading, which indicates there is some civilian government oversight of GAESA’s finances.

Whether GAESA has billions or even hundreds of millions of dollars in cash, given the lack of transparency, couldn’t corrupt officials be siphoning it off for their personal benefit?

The Herald quotes economists suggesting that the lack of transparency makes corruption easier. This is certainly a real risk. But these leaked documents don’t provide any actual evidence of corruption. And if the “cash hoard” as the Herald calls it were being siphoned off either to enrich an elite, or to build up the Cuban military (or both), then we would surely expect more evidence of a sizable class of incredibly rich Cuban officials or a massively well-equipped military. But there simply is no sign of either of those things, and certainly not on the huge scale suggested.

Why doesn’t GAESA just open its books to respond to these critiques?

I think Cuban authorities are aware that they need public trust if they are to have a chance of surviving the current crisis politically, and it doesn’t help when the public knows there are these powerful state-run companies worth many millions of dollars. But the Cuban government is in a bind. With the threat of ever-tightening U.S. sanctions increasing the imperative to keep information on international transactions hidden, the government has no alternative but to utilize offshore businesses, the usefulness of which depends on keeping details of their operations confidential. The lack of transparency is certainly not good for accountability and gives plenty of scope for speculation and misinterpretation, as appears to be the case here, but I don’t think the government has much choice.